In collections, it is not uncommon to encounter an occasional habitual credit abuser or purposeful default that you wish could be thrown in jail. Long before any of us were alive, this was not merely a fantasy, but a grim reality.

Discussing the topic of debtor’s prisons cannot really be done without bringing up the topic of bankruptcy. Debtor’s prisons and compensation to lenders through incarceration had existed for centuries in Europe and carried over into the United States almost immediately.

Great amounts of classic literature exist referencing or using the situation of unpaid debts as the backdrop or centerpiece of their stories. Charles Dickens was inspired to write several classic novels based on the inspiration of his father’s experience of being imprisoned in England’s infamous Marshalsea prison in the early eighteen-twenties while much earlier, in Shakespeare’s King Lear, stories of debt were usually considered tales of immorality or misfortune.

“Neither a borrower nor a lender be;

For loan oft loses both itself and friend,

And borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry.”

Shakespeare, Hamlet 1602

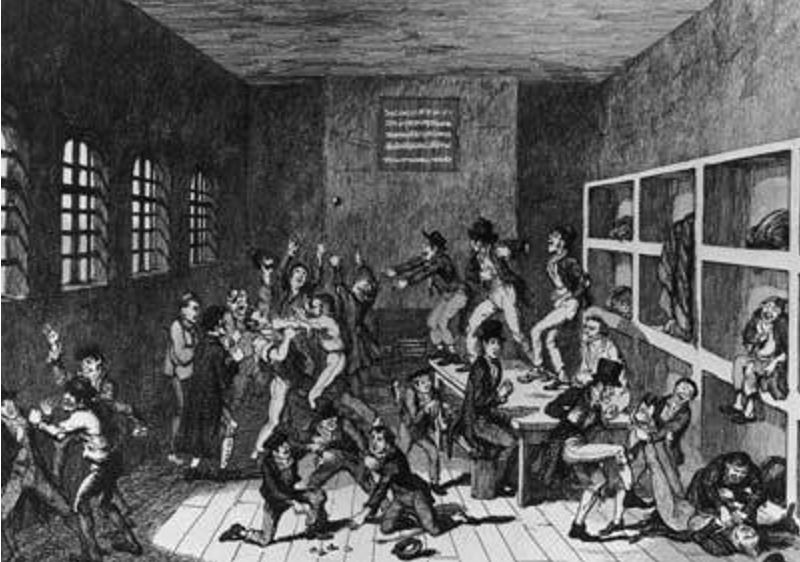

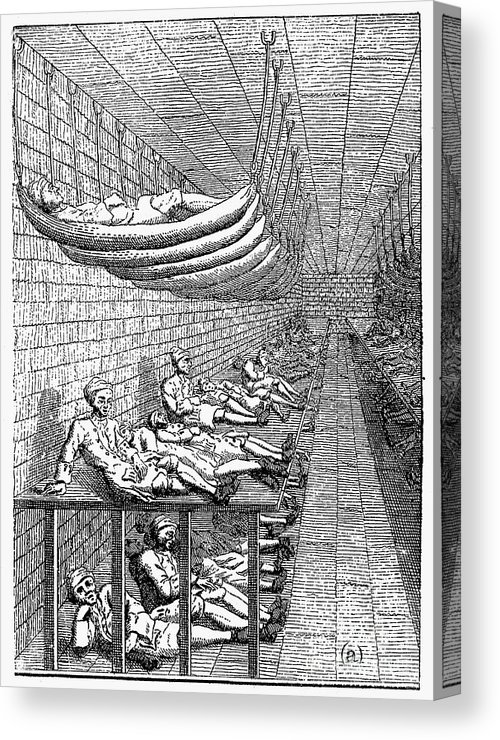

The sad irony of debtor’s prison in its time is that like in medieval prisons, the prisoners were charged for room and board but were expected to repay the debts while provided no means to earn it. Re-compensation, for those lucky enough to pay it, usually came from family members or others with a vested interest in the debtor’s freedom. Any default in these payments would be cause for a discontinuation of feeding and could result in movement to more uncomfortable quarters.

The earliest known record of a debtor’s prison in the Americas goes back to 1678 in Salem Massachusetts. There are estimates that as many as two out of every three Europeans that came to the Americas in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries were debtors as soon as they arrived since many and were serving as indentured servants to pay off the price of their travel to the Americas. There are even some historians that will argue that the American Revolution was a form of debt relief to those indebted to the British Crown over these debts.

Unfortunately, the American revolution did little to improve debt management, or debt punishment as it would be, as exemplified by the common bankruptcy practices in 1785 Pennsylvania, which were to say the least, quite an ordeal. Debtors here were frequently flogged in public and could even be subject to having their ear nailed to a post or just plain cut off. As a form of punitive credit reporting, to assure no one would lend to them again, the old 16th century English Tudor era method identification was often used, where the person filing for bankruptcy was branded on the thumb with a “T” for thief.

As you will see below, debt in colonial America was not merely isolated to the poor and lower classes. There were several prominent early American leaders with a history had debt issues;

Thomas Jefferson, who allegedly at the time of his death in 1826, had accumulated an remarkable for its time, $107K in debt, which required the liquidation of all of his assets to attempt to satisfy huis creditors. If he had survived much longer, he very likely would have found himself as a debt prisoner.

Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, James Wilson, was once jailed in debtor’s prison in 1796 but released after a short time.

A signer of the Declaration of Independence, Robert Morris, was jailed for a number of debts incurred through borrowing unsuccessfully on land speculation deals. Sadly, Morris himself was partially responsible for funding the American Revolution. As illustrated, debt affected all persons alike and the penalties were quite severe.

The Bankruptcy Bill of 1841 allowed for a full discharge of debt unless fifty percent of the lenders opposed. Many of the features of bankruptcy from this bill are still in effect today. This new level of leniency caused an uproar and was repealed thirteen months later.

“Hunt’s Merchant Magazine”, an early American periodical, suggested in 1846 that the dissolution of creditor’s rights and that the remedies of attachment be employed, similar as they are today, would be a more financially responsible and reasonable way to manage debt.

With the absence of credit cards, eighteenth century debts were, for the most “Book Debts”, which are very similar to modern credit with the exception of the compounding of interest, which in its time was considered by most as “usury” and was deemed immoral by biblical and societal standards. Despite the often, draconian collection methods of the times, debtors had the right to the examination of records as well as the presentation of evidence to a court to appeal the court’s ruling for attachment. Surprisingly, even then, creditors were subject to a statute of limitations.

As the methods of debt collection began to standardize and the barbaric conditions of these prisons became the subject of much public discourse, the necessity of debtor’s prison lessened until they were abolished in 1849. Even then, the idea of punitive action for the mere sake of itself was recognized as counterproductive to the alleged goal, which was collecting the debt after all.

Kevin Armstrong

Publisher – CUCollector.com